Defining Scale

“The term ‘scale’ has become so broadly used that it hardly means anything anymore.” - interviewee

Why scaling matters

Scaling is rare. Globally, estimates suggest there’s a .00006 percent chance of building a billion dollar company. Successfully scaling to such levels is truly against the odds, all the more so in Africa where large populations do not equate to potentially addressable markets given the low - and highly skewed - levels of disposable income across the continent, necessitating expansion into new markets very early in a business’ growth cycle.

Serving the base of the pyramid is notoriously hard. There is also competition at the top, with many ventures chasing relatively small, but more wealthy, customer segments. Seeking new markets abroad is highly complex due to the fragmentation which pervades Africa’s mix of 54 different regulatory jurisdictions and cultures.

Yet we know it is these scaled ventures that move the needle in terms of impact, new employment, talent capacity, and overall value creation.

Studies have shown that high-impact entrepreneurs are the cornerstone of rapid, influential growth. Scaling businesses strongly contribute towards innovation, social change, improvement of national competitiveness, and wealth creation. They are more productive than their startup peers, and help to inspire peer companies. They can also contribute to peace and economic transition in emerging markets.

Scale should not be seen as an end-goal but rather as an instrument that actively contributes to addressing economic and societal challenges. Nations with a large number of high-growth entrepreneurial ventures usually have thriving economies. This can be attributed to the role that such enterprises play in creating economic wellbeing. In Africa’s case, whilst fast economic growth is occurring, it is from very low bases. Great care is needed to avoid casting dangerous (inaccurate) comparisons.

Scaling ventures create way more jobs and economic opportunity

Scaling businesses have been linked to disproportionate economic gains over other ventures, such as job creation and economic growth. These companies have also contributed to more innovation and knowledge generation.

Those who are able to scale their businesses can create 100 times more jobs than micro-enterprises, and 10 times more jobs than traditional SMEs. On average, they create more than 200 jobs as their companies grow.

Scaling businesses yield the long-lasting contribution of startups to net job creation. This trend is seen in both developed and emerging markets. In the US, in any given year, the top-performing 1% of young businesses generate roughly 40% of new job creation.

Scaling SMEs in the South African economy account for 50 to 70% of net new jobs.

In Nairobi, the eight software companies that have achieved scale (comprising 1% of the city’s entrepreneurial software companies) have created 40% of the new jobs, and raised more than twice as much funding from venture capital ventures as the other 650 local tech companies combined. This catalytic effect is increased as more companies within the local ecosystem reach scale: 6% of companies in Bangalore in India have achieved scale, and they now generate 90% of the job creation.

Former employees of scaled businesses are more likely to start (and succeed in scaling) new businesses, creating further jobs and opportunity. For example, former employees of Indian unicorn Infosys have started nearly 200 local tech companies in Bangalore alone.

The many meanings of ‘scale’

There are numerous ways in which to measure a scaling venture. Most are blunt.

The standard OECD definition is broad. It suggests scaling businesses are enterprises with average annualised growth greater than 20 percent per annum, over a three year period, with at least 10 employees at the start of the observation.

The Canadian Lazaridis Institute, which helps companies as they grow to global scale, contends that this measure misses the basic premise of scaling, which is to identify and leverage economies of scale. If a venture can achieve this, they increase their potential to grow revenues faster than costs.

Growth can be also measured by the number of (full-time) employees or by turnover per annum, but the metrics used between annualised growth and staff can vary significantly. The Kauffman Foundation also points to minimum revenues of $2m.

What is clear is that growth is highly inhomogeneous, as it is driven by different business models: scaling businesses do not grow in the same way.

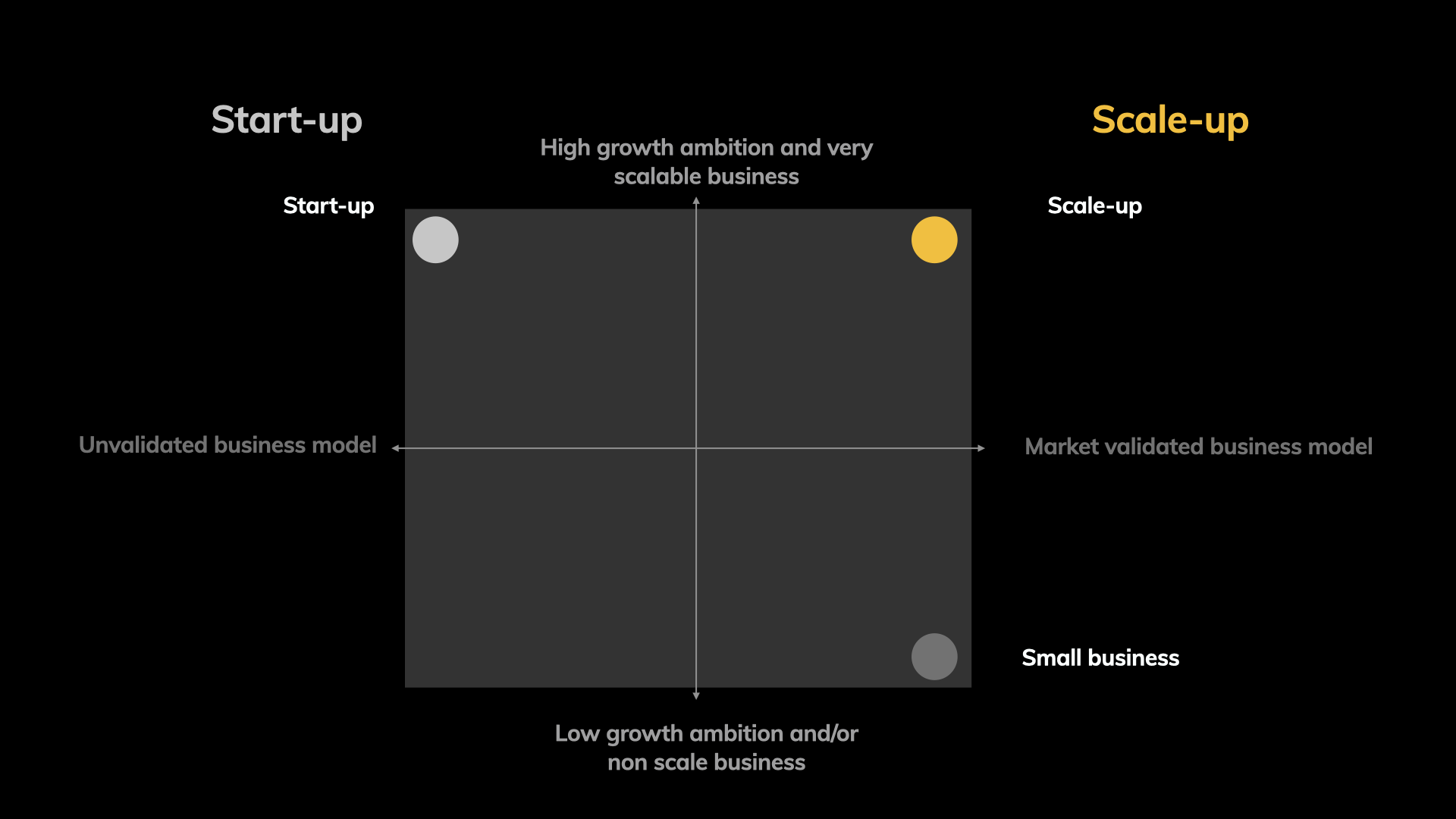

During the earlier stages of a venture’s life, the focus is establishing the business model and product-market fit. Only when a startup objectively demonstrates that this is achieved, and a pattern of revenue generation is clearly identified, does it make sense to scale the business model. Scalability is, after all, the ability to grow quickly without being hindered by constraints imposed upon its business model structure. Figure 7. indicates a simple distinction between a startup and scale-up venture.

Figure 7: Differentiating a startup from a scale-up Source: Startup Commons

Defining African Scaling

The most comprehensive assessment of scale factors in Africa has been developed by the London Business School (LBS), which considers four factors:

number of end users (consumer or business);

annual revenue (US$);

cumulative funds raised (US$); and

and number of employees (the most complete measure).

LBS Professors created a scale index by establishing a threshold for each scale metric based on clearly identified ‘inflection’ points seen in the distribution of scale data and industry input on reasonable thresholds for scale. Companies exceeding this scale threshold on two or more of the four total scale metrics get classified as scaled.

We evaluate their approach as a very useful contribution but also acknowledge it suffers with a narrow design - given the thresholds applied, the index only considers mature scaling ventures. Their range involves:

Companies with 1m+ consumers or 75,000+ business users;

Companies with $20m+ in revenues;

Companies with $15m+ total funding;

Companies with more than 200 employees.

For the purposes of this inquiry, our working definition of scale has been purposely less prescriptive in order to also evaluate early scaling ventures so we can identify their early transition point from startup to scale-up, which typically occurs when the business has successfully:

Achieved product-market fit with a scalable product or service;

Generated revenues;

Hired at least 30 employees (with increasing head-count); and

Demonstrated an average annualised growth greater than 20 percent per annum, over a three-year period.

In general, the ecosystem takes a far less scientific approach as it seeks to count unicorns. And underneath the $1bn valuation, one can ask: what is an African company - one that has an African founder, is listed on the African stock-exchange, has its HQ listed in Africa? And are these businesses still valued at above this threshold (to maintain unicorn status?). There is no common agreement, which leaves the door wide open to inconsistencies and misinterpretations.

Greater scale clarifications via classifications are needed

Both academics and practitioners working in this field argue for clearer definitional efforts. They demand more targeted classifications that allow for more granularity, which in turn can help a better understanding of the ventures under investigation. There are also calls to differentiate between high and low productivity ventures, and high and low skilled ventures. It is important to state that scaling is not synonymous with raising funding per se. Whilst capital helps fuel immediate growth, this does not directly influence what happens to a company after a growth period, and whether growth continues, or whether a venture will subsequently stall (stop or slow down growth).

Alongside the rich influx of funding into the African ecosystem witnessed over the past several years, there has been endless noise fixated on celebrating the success of various funding rounds. Whilst new funding is to be welcomed (and is long overdue), these ecosystem signals offer limited real intelligence (as compared to other basic data points, such as annualised recurring revenues and profits). The ecosystem would benefit greatly from more precision, instead of being drawn towards the (private valuation) hype.

If we look at the field of science, scale really concerns how an organisation changes as it grows, evolves and matures. Author of ‘Scale’, Geoffrey West, has written how companies, like organisms, obey universal dynamics that transcend their individuality and uniqueness: they scale sublinearly (almost, but not quite, linear in shape). He argues that companies follow simple power laws, which are dominated by economies of scale rather than increasing returns and innovation, which has profound implications for their life history, growth, and mortality.

Academics DeSantola and Gulati define scaling as the way in which entrepreneurial ventures deal with the challenge of synchronising internal organising and growth. This definition considers how ventures replicate their business at scale, and how they expand the scope of their activities as they grow. This notion includes organisational design, staffing and organisational culture.

Other researchers have identified four distinct activity configurations, or scale-up modes: network growers, focused scalers, organic innovators, and constricted scalers. Scholars from the Open African Innovation Research partnership (Open AIR) consider a taxonomy of four scaling dimensions: expanding coverage; broadening activities; changing behaviour; and building sustainability.

Professor Tim Weiss begs for focus beyond simply “the speed of roll-out”. We agree and urge the ecosystem to urgently look harder at the questions being posed, and wonder why there has been an absence of precision to date, and whether there is a better way forward than simply relying on funding rounds data (as clearly this is not the optimal nor most sophisticated way forward).

African scale taxonomies are under considered

Notwithstanding that there are more than 1,000 technology ‘hubs’ in Africa, we know relatively little about the mechanics of scaling ventures in Africa. Scaling is a significantly overused label, especially in Africa, where very little attention has been paid to what the term actually means, and how to navigate the complexity associated with the high-growth maturity journey. The word taxonomy concerns the science of classification of living and extinct organisms. To date, scant attention has been offered to understanding, then coding, the growth (and decline) of African ventures.

Studying the scaling process in detail has the potential to yield important insights about how ventures in resource-constrained conditions facing fractured market environments and pervasive informal economies can grow - despite all odds - to medium- and large-sized ventures, and expand internationally.

A formula for scaling does not exist

In an ideal world, there would be a neat formula to apply that could predict scaling. Sadly, this does not exist. Scale Up Nation rightly acknowledges that every scale-up success story is dependent on background, sequence of events, and time- and place-specific context. So, like history, scale-up success does not repeat itself. Moreover, each scaling journey personifies the founders. And finally scaling is organic, interconnected, symbiotic. Like life.

Moreover, given the dynamic nature of the African ecosystem we would warn against the past dictating what the future might hold. But this is not to say the ecosystem cannot improve its approach to be more enlightened about how specific contributions might lead to high-growth success.

Africans are market-creating disruptors, but do not discount legacy issues

The Joseph Schumpeter concept of creative destruction (which refers to the incessant product and process innovation mechanism by which new production units replace outdated ones) is being reframed by African pioneers. Innovators are creating new industries by focusing on solving pain points in ecosystems, and are developing new (mass) markets as a result.

A hopeful (but contestable) view is that Africa is unconstrained: there is a “clean sheet” upon which companies can develop their own distinctive business models and leapfrog. Management firm, PwC, suggests this can be seen in the speed that many markets are expanding, and in the way industry boundaries are blurring (such as the coming together of renewable energy, mobile payment and consumer finance). Whilst this holds true, distinct legacy challenges should not be underestimated.

In the Power of Creative Destruction: Economic Upheaval and the Wealth of Nations, the authors note that innovation is path-dependent: incumbents build on what they know, while newcomers are willing to start afresh. If governments want to ensure rapid innovation in new directions, they need to motivate new players who are not trapped by past successes. Clearer actions beyond simple encouragement will be essential; a range of ecosystem actors also need to get clearer on what supporting roles they will play.

Setting out new pathways to make this happen will be critical to ensure scaling ventures are offered the best conditions to flourish in the future. The arena is ripe for new, innovative, breakthrough thinking.