Investor Ecosystem Snapshot & Shifts

Signposting Strong Progress

The investment ecosystem is still nascent

Access to a range of financing instruments is key in facilitating scale. African-specific studies show that ventures that are not credit constrained experience faster growth than those that are, which justifies the many measures and initiatives being put in place to make more finance available for African ventures.

Notwithstanding recent injections of VC capital, Africa remains an investment frontier from a global perspective. The cost of capital is high. The supply of and demand for capital remains mismatched, due to limited capital availability. Alternative (and more context appropriate) financing models are embryonic. It’s organic and messy, but also rapidly evolving.

“Both on the investment side and the founder side, they're still trying to find their feet in terms of what good looks like in the ecosystem, as far as certain business models are concerned. It's going to take time.” - interviewee

Rapid increase of injections of capital into Africa

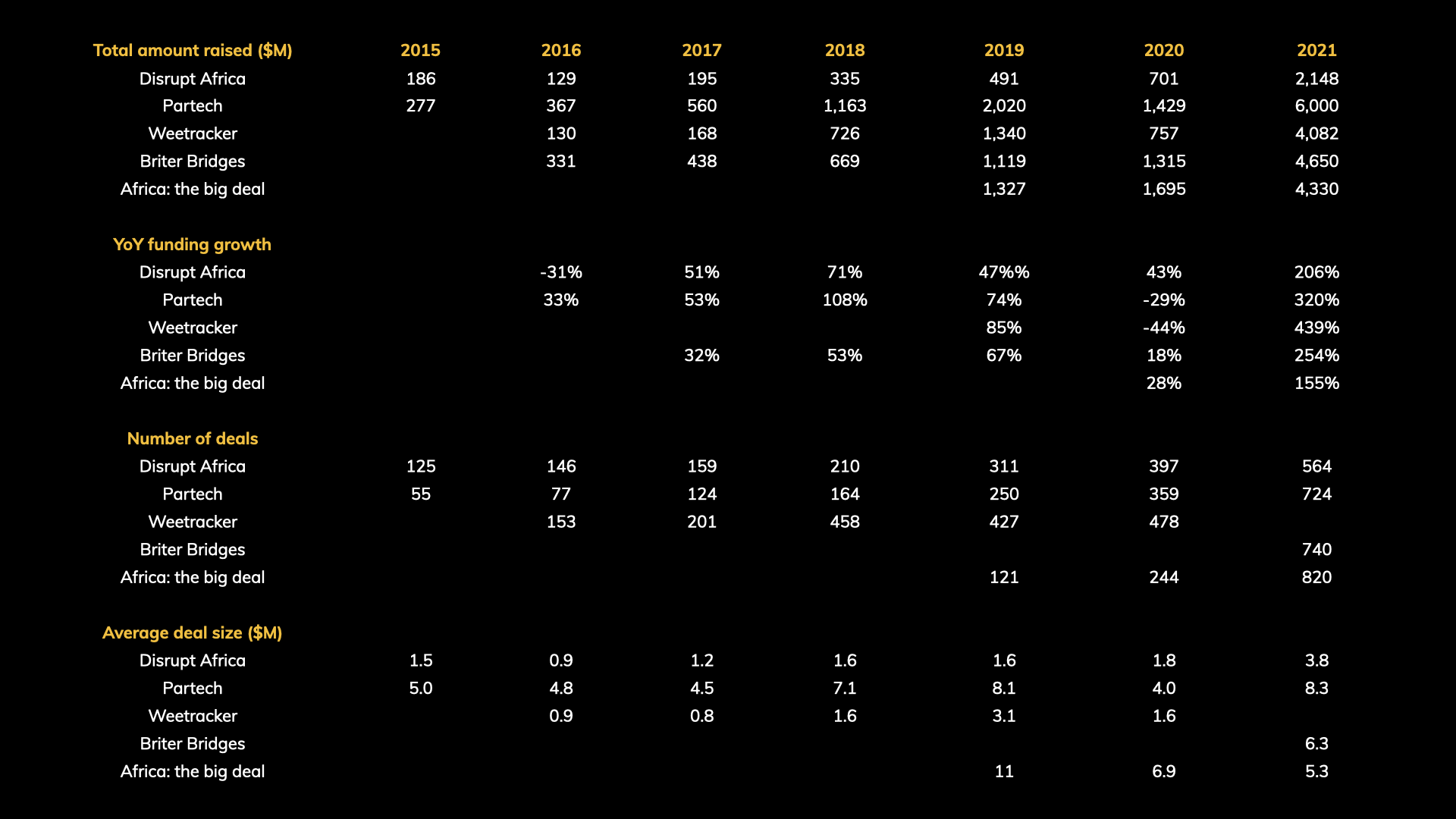

Record funding has entered the African ecosystem over the past 5 years, of which Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya have been the main sub-Saharan beneficiaries. Excellent reporting on capital flows has been made freely available by Briter Bridges, Partech, Disrupt Africa, and The Big Deal, amongst others.

But there are gaping blindspots too, given that 43 percent of early stage funding is undisclosed. This has influenced the large data discrepancies between the different data providers, as seen in Figure 51, in which the estimate of capital raised in 2021 varies from $2.1bn to $6bn.

Figure 51: Ecosystem data discrepancies

The majority of disclosed capital has flowed towards the fintech sector.

Scale up ventures’ funding needs vary significantly. Certain sectors (such as agri and manufacturing), where the capital needs are much greater, have extended runways because of product development and production capacity, which means it takes longer to generate revenues. More money is needed in these areas, especially from institutional investors and development banks.

A recent report on early stage investing in Africa notes that “the problem is that investors exhibit herd behaviour, and are not diverse within their own investment teams”. Showing preferential behaviour for certain sectors limits prospects. It is easy to encourage a higher risk appetite, but there are other alternatives that can also be explored, such as using new systemic design approaches to identify and mitigate risk, vet business models and founders (as investment options), and utilise specific mechanics for sharing risk via syndicated models.

Foreign investors are now also becoming increasingly attracted to the continent.

“The big VC names, most of them, as of last two years, are now involved. From SoftBank to General Atlantic.”- interviewee

Much of the foreign investment is coming from American, Asian and European VC funds who are seeking to build local presence in new markets and take bigger bets, which a local VC we interviewed sees as “absolutely the right approach, if they're going to double down on the continent.”

Whilst the trends over the past few years have been very positive, unknowns remain. With global venture capital funding cooling down in Q1 2022, this has raised concerns about what this means for the African ecosystem. Y Combinator recently warned founders in their portfolios to “plan for the worst” as startups across the globe scramble to navigate a sharp reversal after a 13 year bull run. Other stakeholders are more buoyant.

Continuously injecting more capital into the ecosystem is essential to ensure that further scaling and growth occur. But capital alone will likely only result in limited outcomes, given the ecosystem’s nascency coupled with the massive socio-economic contextual barriers influencing it. Investors need to ensure their capital allocations are packaged with a range of additional support and technical assistance (which we call ‘Capital Plus’, and describe below) to reduce risk and increase probability of success and bigger returns on investment.

Local African VCs are rising

Former successful entrepreneurs are increasingly investing in angel networks and venture capital funds. Often such capital partners are capable of assisting with both funding and knowledge, experience and expert advice to facilitate and accelerate a company’s transition from startup to scale-up.

“African investors are now actually providing resources for African founders.” - interviewee

Parallel to the exponential growth in foreign funding in recent years is the rise of local venture capital, particularly early stage funding. This increased interest is a result of:

A rapidly developing technology landscape that has (recently) yielded many investable opportunities;

More success stories, including African unicorns, attracting foreign investor interest; and

A proliferation of new hybrid models that combine elements of angel investing, crowdfunding and venture capital, with faster due diligence, more reliance on data, and more of a focus on upside rather than downside risk.

African investors understand the unique operational mechanics of their societies, and have the benefit of existing local networks and expertise. They are more likely to take risks where Silicon Valley style investors might baulk. By de-risking the early stage, the door is opened for foreign investors and their big(ger) cheque books. Organic investor segmentation also reduces the risk of global investors crowding out local VCs.

It’s not all unicorns and rainbows though. There is chatter on the proverbial backbenches on the need for local VCs to up their games, and ensure that their dealings with founders are fair and equitable:

“The other thing that tends to be damaging - and we've got a number of such VCs - who fit the check to the reality of their fund size. Say I want to play in Series A, but I only have $50,000. I'm going to take 20% of your business for $50,000. But it's not how it works.” - interviewee

“The founders need to be told, ‘Hey do not take a local cheque’. Here are the minimums you need to take when you're asking for money. You need to ask for 36 months runway, you need to have a plan for that, you need to show how much growth you can really show (and be pessimistic, not optimistic).” - interviewee

Although many of the larger cheques are being written by foreign investors, local VCs are becoming increasingly prominent in the overall deal count, especially Launch Africa, Future Africa and LoftyInc Capital, as indicated by Figure 52, which indicates the most active investors by deal count in 2021.

Figure 52: Equity Deal numbers ($100K+) 2021. Source: Chart: Rest of the World, Data The Big Deal

Founders and scale-up executives are becoming angel investors

Increasingly, local investors are themselves former founders and scale-up executives. They have been-there-done-that, in the same local contexts, and are uniquely placed to nurture the next generation of founders. Whilst their value may seem intuitive, studies have also confirmed it: in one large study, receiving experience, mentorship, or investment from an entrepreneur who has led a company to scale is associated with approximately two times greater prevalence of top performance. This has a cascading effect on the ecosystem, as more former founders repeat the pattern.

These industry doyens understand the nuances of the challenges and market potential of new tech models better than the average angel investor. As a result, they are able to make quicker investment decisions, which is helpful for both entrepreneurs and the ecosystem, as their actions have knock-on effects on other angel and early stage investors, who are traditionally a bit slow off the mark.

According to ABAN, founders of scale-ups (including those of Flutterwave, Paystack and Andela) were among the most active early stage investors in 2021. (While there is lots of goodwill toward founders giving back to the ecosystem, let’s not forget that there’s plenty in it for them too.)

Africa’s Y Combinator presence is firmly rooted

African firms are now relatively well-represented at the famed Silicon Valley startup accelerator Y Combinator, which encourages a blitzscaling model. In March, Nigerian startups were better represented than those of any other country, except two. The dedicated strategic support from Future Africa, which has helped enable this shift, needs to be acknowledged. Y Combinator stats (as at March 2022), reported by Techpoint Africa, indicate the movement:

YC has invested in 95 African startups.

Nigeria has the largest share of YC-backed African startups, with 51 out of 95.

As of March 2022, YC-backed startups on the continent have raised $1.3 billion.

86% of the African startups that have participated in the accelerator were in the first two years of their establishment.

Out of the 95 African startups, only 19 have individually raised $10 million and above.

African YC-backed startups jointly have over 6,193 employees.

Most YC-backed African companies were founded in 2020. Interestingly, only three got into the accelerator that year, while others made it into the 2021 winter and summer cohorts.

Most of the African startups that participated in the accelerator are in the fintech sector.

Briter Bridges has helpfully profiled the YC-backed African startups. Y Combinator has standardised vetting and investment processes, including using the Simple Agreement for Future Equity (SAFE) model (which YC conceptualised in 2013 and which reduces costs, time and complexity of early stage investing mechanics). One of our recommendations is the adoption of SAFEs as an industry norm, as is happening in other parts of the world.

Bigger, faster funding rounds are more common

The ecosystem is seeing bigger deal sizes - at later stages, and faster - than previous years. These are positive signals of a maturing ecosystem. Encouragingly, leading early stage funds have been tweaking their funding mechanisms to keep pace with the market and ensure smoother deal flow.

“What I hope happens with these global funds coming into Africa is that it creates the certainty for early stage local investors that they're going to be able to realise a return on their early investment, and so they become more active at the earlier stage on better terms, so they don't have to price it as much as they do today. What that should mean then is that startups get better support earlier, that is contextually relevant to the markets they're operating in, but are able to raise the kind of volume of capital that they need to scale at the time that they are scaling.” - interviewee

In a high-risk investment environment like Africa, investors stick to tried-and-tested approaches which they believe work. With an influx of foreign investors, there will accordingly be a tendency to adopt the Silicon Valley “replicate and adapt” model, including the investor expectations that are attached to this. A hybrid model that engages African resources to localise the model in-situ is starting to emerge, which is encouraging.

“What we have also seen is international investors that want to provide resources on the ground partnering with local investors, and also leveraging local resources to provide that. So it’s not necessarily Africanised - but I think people are realising that you can't just come with the Americanised, Silicon Valley model. I think people are realising that you cannot just copy and paste models from one place into a different environment, or fail to hire locals to bring in a local mindset to interact with these local entrepreneurs, or partner with local companies, especially if they haven’t already done this for a longer term.” - interviewee

New African investment markets are emerging

With $2.5bn raised collectively, the Top 50 deals ($10m & over) are responsible for 83 percent of the total amount raised by startups in Africa in 2021. Much of this capital is directed to firms in large markets (Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa), with far smaller sums flowing into firms from Ghana, Senegal and Tanzania.

Whilst investment outside of the ‘Big 3’ countries is limited, it’s growing fast year on year, a trend we anticipate will continue provided that talent and capital gaps are overcome. There is a ripe opportunity for stakeholders to develop the ‘up-and-coming’ country markets differently to the Big 3, learning from mistakes made and lessons learnt, which we actively encourage.

Traditional lenders remain cautious about extending credit

In developed markets, traditional loans from banks are usually a funding option, which has the obvious advantage that owners do not have to give up ownership and control of the company. This is less so in Africa where securing credit is notoriously hard. Many African banks invest large sums abroad, and lend relatively little to local businesses. African SMEs receive just 10 percent of commercial bank lending.

African businesses appear unattractive due to high levels of perceived risks. This translates into a reluctance to lend. The lending which occurs happens at high interest rates, for short terms, and very demanding collateral requirements. A report from the think-tank Chatham House proposes that banks and lenders need to be patient and have a long-term view of ROI in order to be catalysts for scaling. They advise that institutions move away from short-term, high interest loans. Whilst banks have tended to support savings and mobile banking expansion, they have not yet improved lending to SMEs to facilitate scaling.

Evidence shows, however, that de-risking mechanisms, such as credit guarantees, are an insufficient solution if they are limited to banks: it is essential to provide support to local non-bank capital providers and financial intermediaries. A growing number of non-bank lenders in Africa - local debt funds, fintech firms, supply chain finance, lease finance providers and other financial intermediaries - have already developed a track record of providing the types of flexible, affordable, longer-term financing that small businesses need, often pairing financing with supportive technical assistance. They have shown that they understand and can manage the perceived versus actual risks of early-stage investment and have the flexibility to tailor financial instruments to support businesses’ working and growth capital needs. Yet they still have, to date, insufficient access to capital and technical expertise to enable scaling.

Increasing M&A activity will create new exit opportunities

Nicole Dunn from Founders Factory Africa has noted the increased merger and acquisition (M&A) activity on the continent, with several high profile global exits via acquisitions (rather than IPOs), including Stripe acquiring Paystack, World Remit acquiring Sendwave, and Network International acquiring DPO Group. She notes that there are also some examples of Africa-Africa startup acquisitions. M&A deals grew to 33 transactions in 2021 (up from 17 in 2020), and have started to influence Africa's exit landscape.

Future Africa anticipates that African startups post-Series C are likely to explore inorganic growth methods such as M&A in order to ramp up growth and expansion. This is especially true for companies in financial services where there is a lot of overlap in solutions and investments. Earlier exit opportunities, as a result of more M&A deals, will both attract new investors to the continent, and increase liquidity (and availability) of early stage funding within local ecosystems.

Venture debt is featuring more prominently

Equity funding is not the only path to building a business on the continent. Equity investment can in fact be a limiting factor: according to Village Capital, equity is not always the best model for all entrepreneurs, and can encourage a dangerous “grow at all costs” mentality.

While debt funding remains widely under-reported and undisclosed, it is growing to prominence in the fundraising strategy of African ventures. As the ecosystem matures, funding alternatives like debt become viable.

Venture debt may be a more appropriate form of investment for some early stage ventures, particularly in markets with limited M&A activity and other means of exit. The advantage over equity financing is that founders do not have to cede large portions of their company to equity investors. Venture debt is therefore a useful mechanism for earlier stage ventures to use to work around the trend we are seeing of smaller, local early-stage VCs demanding more equity than their investment is worth, which limits opportunities for these ventures to secure bigger funding at Series A and B, if much of the equity has already gone to small-scale earlier stage investors.

That being said, companies with non-transferable intangible assets would likely struggle to obtain debt finance (other than short-term debt financing backed by inventory). Industries with debt-friendly assets or business models have a better chance of accessing this financing source. This includes sectors like renewable energy, where solar panels and supply contracts can give debt investors comfort that they will be repaid.

Whilst one would think that banks would be a key venture debt partner, the high interest rates act as a deterrent, as does the inherent lack of trust of banks embedded in many African cultures. In Ghana, for example, most entrepreneurs in the energy sector prefer not to borrow funds from commercial banks, due to socio-cultural factors.

Strategic debt players have begun launching dedicated debt funds targeting emerging markets, especially in Africa. Once the models become reliable and the product-market fit is rooted, debt investors become more open to funding ventures. Based on the ongoing trend, many believe that Africa is poised to witness a surge in founders seeking debt financing for their startups in the coming years.

Alternative sources of capital are generally increasing

Interestingly, international studies indicate that ventures that use both formal and informal finance have the highest chance of becoming a high-growth venture. They may also perform much better than their counterparts.

As noted by Amma Gyampo, co-founder of ScaleUp Africa and a member of the advisory board for this project, much of the African investment narrative has centred around the difficulty in finding exit opportunities. She recommends that investors go back to basics, take a demand-driven, innovation-focused approach, and do the work required to ensure that they are backing robust sustainable businesses, rather than “creating bubbles that fuel unicorn chasing and inevitable busts”.

Alternative models we feel have particular application in the African context include the following:

Crowdfunding is an important source of funding supporting early growth, especially as a mechanism to attract diaspora investment. Risks include forced exit and lower returns. Better oversight (and perhaps regulation) of the crowdfunding model are needed though, all the more so in light of multiple fraud allegations in Nigeria, especially in the agribusiness vertical.

Funds should also consider adopting more flexible structures that are more responsive to market-level changes. In her excellent report Chasing Outliers, Tayo Akinyemi suggests that permanent capital vehicles (PCVs), such as endowments, is one approach. The open-ended time frame that characterises PCVs is a notable benefit, allowing companies to fully realise their growth potential. Nonetheless, some would argue that time horizon and liquidity preferences are difficult to reconcile within PCVs, especially given that VC fund investors, namely a fund’s limited partners, want a return of capital and exit within a defined period of time, usually 8 to 12 years.

Revenue-sharing through financing assets is another innovative alternative approach. Untapped Global's Smart Asset Financing model is used to invest in the venture’s productive assets (i.e. the ones that they use to make money) and generates its return through revenue sharing: they take a percentage of the revenue that is generated from the use of the assets that they finance. Their team member told us that she sees that as a way “to take the risk with the entrepreneur and with the company. And, over time, we've proven that the model works for us to get our return over a period of time.”

We encourage greater diversity in funding, as we believe this will increase the amount of available capital within the ecosystem. If there are options aside from typical equity funding for founders to explore, especially at the early stage, it will also help to level the playing fields between investors and investee ventures.